What is the Nomad Protocol?

Nomad is a new design for radically cheaper cross-chain communication without header verification. We expect operating Nomad to cut 90% of gas costs compared to a traditional header relay. To accomplish this, we took inspiration from optimistic systems (a la Optimistic Roll-ups). Nomad features many of the features we prize in an optimistic mechanism, like public verification, low gas fees, broad participation, but has a slightly different security model.

Nomad will form the base layer of a cross-chain communication network that provides fast, cheap communication for all smart contract chains and rollups. It relies only on widely-available cryptographic primitives (unlike header relays), has a latency of thirty minutes (rather than an ORU’s one week latency), and imposes only about 120,000 gas overhead on message senders.

Nomad has been designed for ease of implementation in any blockchain that supports user-defined computations. We will provide initial Solidity implementations of the on-chain contracts, and Rust implementations of the off-chain system agents.

Nomad is an implementation and extension of the Optics protocol (OPTimistic Interchain Communication).

Building Intuition for Nomad

Nomad works something like a notary service.

The sending (or “home”) chain produces a series of documents ("messages") that needs notarization. A notary (called the “updater”) is contracted to sign it. The notary can produce a fraudulent copy, but they will be punished by having their bond and license publicly revoked. When this happens, everyone relying on the notary learns that the notary is malicious. All the notary's customers can immediately block the notary and prevent any malicious access to their accounts.

How does Nomad work?

Nomad is patterned after optimistic systems. It sees an attestation of some data, and accepts it as valid after a timer elapses. While the timer is running, honest participants have a chance to respond to the attestation and/or submit fraud proofs.

Unlike most optimistic systems, Nomad spans multiple chains. The sending chain is the source of truth, and contains the “Home” contract where messages are enqueued. Messages are committed to in a merkle tree (the “message tree”). The root of this tree is notarized by the updater and relayed to the receiving chain in an “update”. Updates are signed by the updater. They commit to the previous root and a new root.

Any chain can maintain a “Replica” contract, which holds knowledge of the updater and the current root. Signed updates are held by the Replica, and accepted after a timeout. The Replica effectively replays a series of updates to reach the same root as the Home chain. Because the root commits to the message tree, once the root has been transmitted this way, the message can be proven and processed.

This leaves open the possibility that the Updater signs a fraudulent update. Unlike an optimistic rollup, Nomad permits fraud. This is the single most important change to the security model. Importantly, fraud can always be proven to the Home contract on the sending chain. Because of this, the updater must submit a bonded stake on the sending chain. Fraud can always be proven on the sending chain, and the bond can be slashed as punishment.

Unfortunately, certain types of fraud can't be objectively proven on the receiving chain; Replicas can't know which messages the home chain intended to send and therefore can't check message tree validity in all cases. However, if a message is falsified by an Updater and submitted to the Replica, that update is public. This means that any honest actor can prove this fraud on the original Home contract and cause slashing. There is no way to hide fraud.

In addition, because the Replica waits to process messages, Nomad guarantees that honest dapps can always prevent processing of dishonest messages. Fraud is always public knowledge before the fraudulent message is processed. In this sense, Nomad (like atomic swaps and other locally verified systems) includes a requirement for honest users to stay online. We have built a robust system for delegating this responsibility.

All off-chain observers can be immediately convinced of fraud (as they can check the home chain). This means that the validity of a message sent by Nomad is not 100% guaranteed.

Instead, Nomad guarantees the following:

Fraud is costly

All users can learn about fraud

All users can block a fraudulent message before they are accepted

In other words, rather than using a globally verifiable fraud-proof, Nomad relies on local verification by participants. This tradeoff allows Nomad to save 90% on gas fees compared to pessimistic relays, while still maintaining a high degree of security.

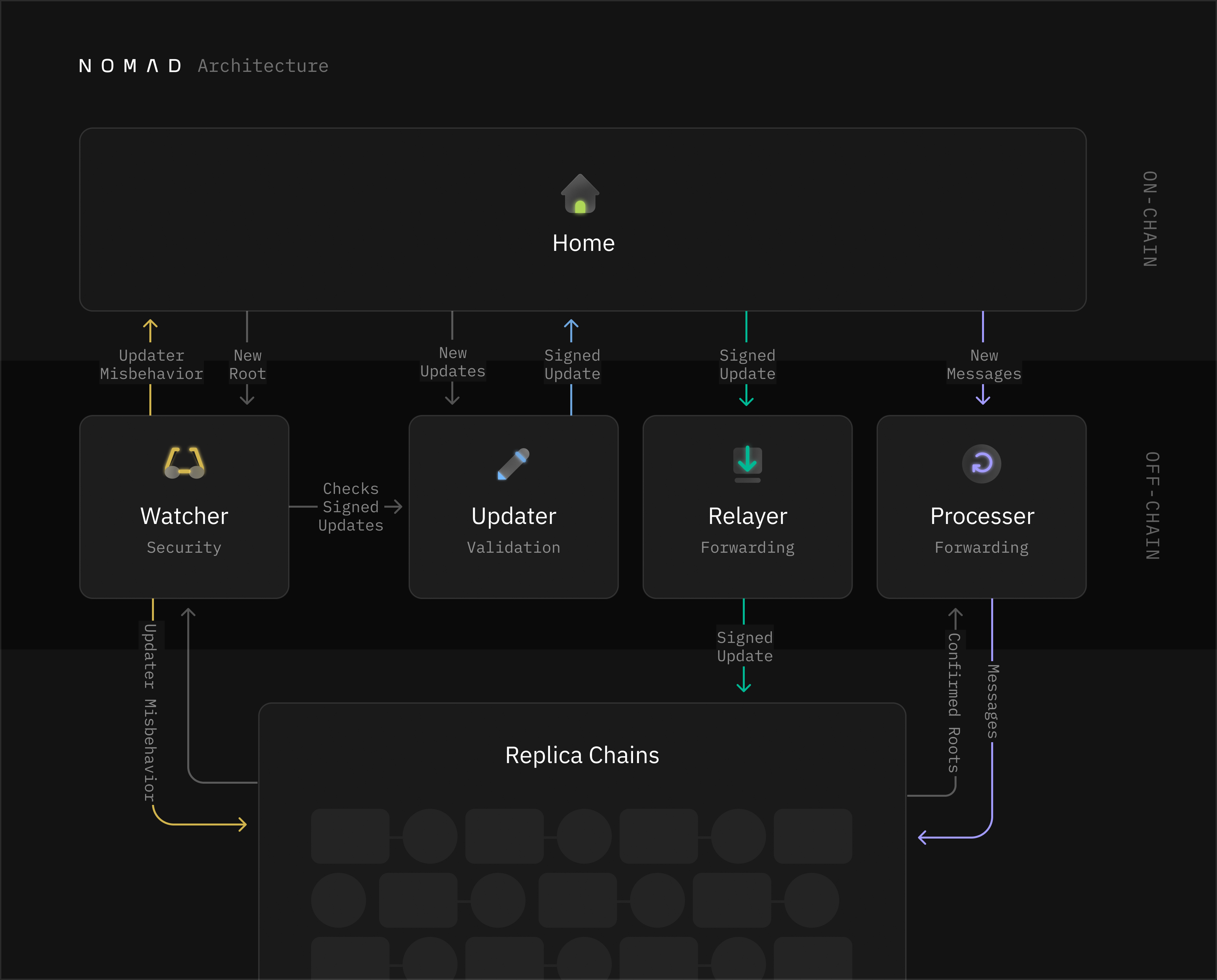

Nomad Architecture

Nomad contains several on-chain and off-chain components. For convenience, we’ll be referring to the Home and Replica as contracts, when in fact they are several contracts working together.

On-chain (Contracts)

Home

The home contract is responsible for managing production of the message tree and holding custody of the updater bond.

It performs the following functions:

- Expose a "send message" API to other contracts on the home chain

- Enforce the message format

- Commit messages to the message tree

- Maintain a queue of tree roots

- Slash the updater's bond

- Double-update proofs

- Improper update proofs

Replica

The replica contract is responsible for managing optimistic replication and dispatching messages to end recipients.

It performs the following functions:

- Maintain a queue of pending updates

- Finalize updates as their timeouts elapse

- Accept double-update proofs

- Validate message inclusion proofs

- Enforce the message format

- Dispatch messages to their destination

Off-chain (Agents)

Updater

The updater is responsible for signing attestations of new roots.

It is an off-chain actor that does the following:

- Observe the home chain contract

- Sign attestations to new roots

- Publish the signed attestation to the home chain

Watcher

The watcher observes the Updater's interactions with the Home contract (by watching the Home contract) and reacts to malicious or faulty attestations. It also observes any number of replicas to ensure the Updater does not bypass the Home and go straight to a replica.

It is an off-chain actor that does the following:

- Observe the home

- Observe 1 or more replicas

- Maintain a DB of seen updates

- Submit double-update proofs

- Submit invalid update proofs

- If configured, issue an emergency halt transaction

Relayer

The relayer forwards updates from the home to one or more replicas.

It is an off-chain actor that does the following:

- Observe the home

- Observe 1 or more replicas

- Polls home for new signed updates (since replica's current root) and submits them to replica

- Polls replica for confirmable updates (that have passed their optimistic time window) and confirms if available (updating replica's current root)

Processor

The processor proves the validity of pending messages and sends them to end recipients.

It is an off-chain actor that does the following:

- Observe the home

- Maintain local merkle tree with all leaves

- Observe 1 or more replicas

- Maintain list of messages corresponding to each leaf

- Generate and submit merkle proofs for pending (unproven) messages

- Dispatch proven messages to end recipients

How Nomad passes messages between chains

Nomad creates an authenticated data structure on a home chain, and relays updates to that data structure on any number of replicas. As a result, the home chain and all replicas will agree on the state of the data structure. By embedding data ("messages") in this data structure we can propagate it between chains with a high degree of confidence.

The home chain enforces rules on the creation of this data structure. In the current design, this data structure is a sparse merkle tree based on the design used in the eth2 deposit contract. This tree commits to the vector of all previous messages. The home chain enforces an addressing and message scheme for messages and calculates the tree root. This root will be propagated to the replicas. The home chain maintains a queue of roots (one for each message).

The home chain elects an "updater" that must attest to the state of the message tree. The updater places a bond on the home chain and is required to periodically sign attestations (updates or U). Each attestation contains the root from the previous attestation (U_prev), and a new root (U_new).

The home chain slashes when it sees two conflicting updates (U_i and U_i' where U_i_prev == U_i'_prev && U_i_new != U_i'_new) or a single update where U_new is not an element of the queue. The new root MUST be a member of the queue. E.g a list of updates U_1...U_i should follow the form [(A, B), (B, C), (C, D)...].

Semantically, updates represent a batch commitment to the messages between the two roots. Updates contain one or more messages that ought to be propagated to the replica chain. Updates may occur at any frequency, as often as once per message. Because updates are chain-independent, any home chain update may be presented to any replica, and any replica update may be presented to the home chain. In other words, data availability of signed updates is guaranteed by each chain.

Before accepting an update, a replica places it into a queue of pending updates. Each update must wait for some time parameter before being accepted. While a replica can't know that an update is certainly valid, the waiting system guarantees that fraud is publicly visible on the home chain before being accepted by the replica. In other words, the security guarantee of the system is that all frauds may be published by any participant, all published frauds may be slashed, and all participants have a window to react to any fraud. Therefore updates that are not blacklisted by participants are sufficiently trustworthy for the replica to accept.

Nomad Channels for Cross-Chain Communication

Nomad sends messages from one chain to another in the form of raw bytes. A cross-chain application that wishes to use Nomad will need to define the rules for sending and receiving messages for its use case.

Each cross-chain application must implement its own messaging protocol. By convention, we call the contracts that implement this protocol the application's Router contracts. Their function is broadly similar to routers in local networks. They ensure that incoming and outgoing messages are in the protocol-defined format, and facilitate handling and dispatch.

These Router contracts must:

maintain a permissioned set of the contract(s) on remote chains from which it will accept messages via Nomad — this could be a single owner of the application on one chain; it could be a registry of other applications implementing the same rules on various chains

encode messages in a standardized format, so they can be decoded by the Router contract on the destination chain

handle messages from remote Router contracts

dispatch messages to remote Router contracts

By implementing these pieces of functionality within a Router contract and deploying it across multiple chains, we create a working cross-chain application using a common language and set of rules. Applications of this kind may use Nomad as the cross-chain courier for sending and receiving messages to each other.

Benefits and Trade-offs of the Nomad Architecture

| Benefits | Challenges |

|---|---|

| Broadcast channel | 1-of-N fraud-proof trust model |

| Cheap | Liveness failure if updater goes down |

| One-solution fits all | Updater could voluntarily forfeit bond to try to pass forged messages |

| Simple |

The benefit of Nomad is that the broadcast channel allows for a single-producer, multi-consumer model. This ensures that 1 accumulator can communicate with any number of receiving chains. It’s also much cheaper than other options, allowing updates and proofs to cost <100k gas and be checked by only 1 signature. With Nomad, one-solution fits all meaning that constraints on receiving chains are minimal (1 hash function + 1 signature check). There is no implementation or security difference between Proof of Stake and Proof of Work chains. There is also many fewer LoC than a Relay, much lower design maintenance overhead, and much less expertise required to maintain and operate.

We’ve been careful to address all concerns with the Nomad system and have designed solutions that allow for optimal speed, cost, and security of the network. For example, we rely on fraud publication rather than fraud proofs to improve the speed and cost of sending messages. In this security model, any potential fraud is disincentivized and costly, and all participants will always learn of any potential fraud with plenty of time to mitigate harm.

Governance

Nomad will roll out its finalized governance process and signer composition in April 2022.

Governor

Policy: 3 of 5 - of the five total signers, three signatures are required to execute a transaction

Signers:

- Layne Haber:

0xC69b66cc2811B509829448FBFfb2553c4CBb627e - Praneeth Srikanti:

0x9bdD76b2a69Db43Fa695a10f5977b8FD891225f3 - Pranay Mohan:

0xab0614cE8d53ea2c67B87f8ad4d8Fac7A4a516e5 - Anna Carroll:

0x25270d2e6980C5b343C4866Aea904a9A9bCA733F - Katherine Wu:

0x83865712c50f702fA4650C7fadEd90A54242046e

Ethereum Recovery Manager

Policy: 2 of 3 - of the three total signers, two signatures are required to execute a transaction

Signers:

- Eli Krenzke:

0x347Ae1a35BED71BB796A5279CD85FED964468aE9 - Barbara Liau:

0xDE9cfb1216889Dee0cAB8afB04c63911427659E4 - Conner Swann:

0xea24Ac04DEFb338CA8595C3750E20166F3b4998A

Moonbeam Recovery Manager

Policy: 3 of 5 - of the five total signers, three signatures are required to execute a transaction

Signers:

- Barbara Liau:

0xDE9cfb1216889Dee0cAB8afB04c63911427659E4 - Conner Swann:

0xea24Ac04DEFb338CA8595C3750E20166F3b4998A - Alberto Viera:

0x4E8ee1AEFEf37c431c6B68F1F5fE6e309ba44376 - Arthur Kaseman:

0x9A23197B7d8bA57E8fe62c3047003C8854F688Cc - Aaron Evans:

0x3DfED02fEFDDA06A80E21f35097fb910a4a790ef